By Dr. Stacey Patton

Yesterday, The Times of Trenton officially announced that I will receive the 2012 Barbara Boggs Sigmund Award from Womanspace of Mercer County, NJ. This recognition has been bestowed on 18 stellar women, including artist Faith Ringgold, television personality Star Jones, journalist Diane Sawyer, and Rutgers University basketball coach C. Vivian Stringer.

To be honest, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that Womanspace selected me to receive its annual for my work on behalf of children who have been abused or neglected.

It’s always nice to be recognized for your work, especially when it’s work you do from the heart. While my “official” professions are author, journalist and historian, my “passion project” is speaking to and working with youth and adults around issues of foster care, adoption, and domestic violence.

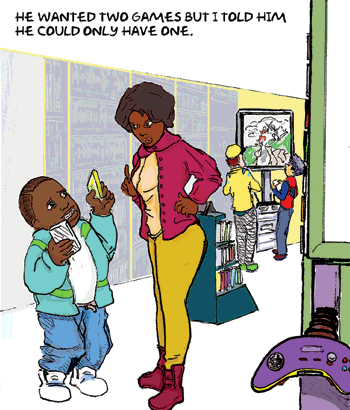

As you know, I am one who includes the spanking of children—corporal punishment in the name of discipline—in my definition of domestic violence. When I share this perspective, and my commitment to giving parents options to use in their child-rearing toolkit, some people react very negatively. I’ve received countless insults, typed attacks and threats on this site and elsewhere for suggesting that physical violence might not be the best way to communicate with a child.

Maybe it shouldn’t be a surprise that some of those people who are most adamant about spanking and beating children (you know, the ones who loudly and proudly advocate “whuppin’ that a**”) often have hostile reactions to my advocacy work.

Fending off attacks is nothing new for me: I spent my childhood trying to survive an abusive adopted home. So the vicious comments and accusations only fuel my determination to grow this movement until the beating of children is viewed as socially unacceptable.

So in addition to being an honor, I appreciate Womanspace’s recognition of my work, not only because I have deep respect for their organization, but because it is so profoundly validating of my efforts to make a difference. This is especially important these days when, despite rhetoric to the contrary, the well-being of kids is not a national priority.

The Children’s Defense Fund reports that Black children are facing the worst crisis in America since slavery. Their statistics paint a grim and frightening portrait of young Black life in our nation. There are many areas for progress and improvement: health, education, poverty, fractured family structure, and risk of crime and incarceration. Why then would we add corporal punishment to the already daunting load of challenges faced by Black children today?

Womanspace is a nonprofit that provides help for victims and survivors of domestic and sexual violence, and they have upgraded their child advocacy program this year into a full-service therapeutic children’s counseling division. They get it!

I will humbly and gratefully accept their Barbara Boggs Sigmund Award on behalf of every parent who has struggled with anger, fear and frustration; every child who wonders why the person they rely on for survival is hurting them to “teach you a lesson;” on behalf of the countless women and men in social services; and in tribute to those advocates and activists who came before me. It means a lot to me, for all those reasons.

But the most important message that this honor conveys is that, despite the often hateful response to standing up for children, I am not alone in this struggle, the most important of my life.

The Womanspace fundraiser will be held on May 9, in the Westin Hotel at Forrestal Village. Please help support their work by purchasing a ticket, or making a donation at www.womanspace.org, or calling them at 609.394.0136.

Recent Comments