People write me all the time and say, “Mother Wit, I don’t know what’s wrong with my child.” “My child has lost his mind.” Or, “I just can’t seem to understand why my child does some of the crazy things she does.”

People write me all the time and say, “Mother Wit, I don’t know what’s wrong with my child.” “My child has lost his mind.” Or, “I just can’t seem to understand why my child does some of the crazy things she does.”

Let me tell you something, I’ve been there with my own kids and so I feel the frustration. I swear, there were times when my kids pushed me to the point when I felt like I could have strangled them.

But over the years I’ve come to realize that a child’s main job is to figure out how to find their way in this big challenging world and to figure out how things work. And what that means is that as they grow up they will test their parents and see what lines they can get away with crossing.

Now, I know this is frustrating to all you parents and guardians out there. But you must remember that acting up at home, in school, or out in public is perfectly normal behavior. Sometimes misbehaving is a sign that they are growing up and trying to establish their independence from you.

When I was a young single parent raising my kids I didn’t know much about the different stages of child development and so I often responded to my kid’s behaviors in ways that were not always appropriate, healthy, or effective. A lot of times I disciplined them from a place of fear, because I didn’t know any better, and because I didn’t have the right tools. But more importantly, I had no basic understanding of why children misbehave in the first place. So now that I’m a grandmomma and I’ve learned from many of my own parenting missteps, I’d like to share with you a few tips you need to keep in mind that will help you understand why kids act up.

1.Children want your attention.

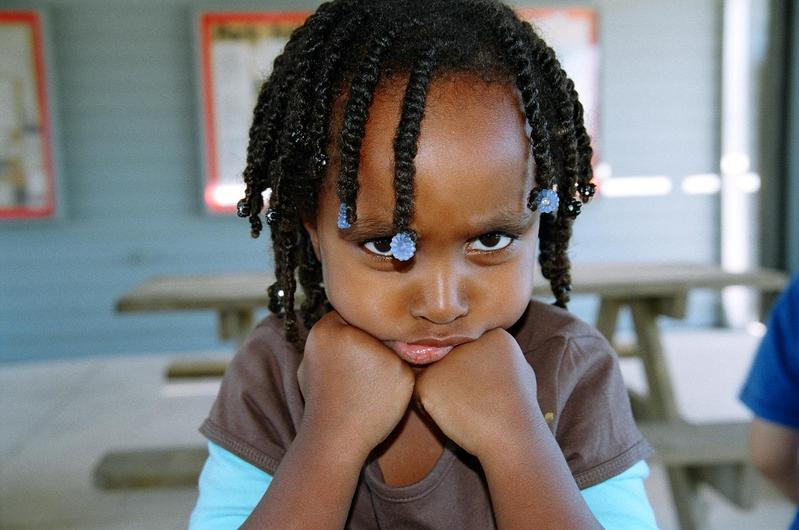

When my grandbabies act up, I know they are doing it to get my attention. Sometimes they might be feeling a little anxious, bored, insecure, hungry, tired or uncomfortable because their needs might not be getting met.

I think that sometimes they have mistaken beliefs about their relationship with me. So they test me to see if I really believe the things I say to them. I have to remember to be firm and consistent. That doesn’t mean that I have to holler and do a lot of talk, talk, talking. I find that talking about what I’m going to do if they don’t act right doesn’t do much good. It only gives them the attention they want from you.

You need to have your mind set on what YOU will do, not what you will try to make your child do. What I try to do is ignore the misbehaviors (be reasonable about it though) and try to get them to do behaviors that are useful for or else. Now, for me, “or else” means that I will impose some logical, non-violent consequences for their behavior.

2.Children don’t always know what is expected of them.

As I said earlier, when I was raising my kids I had little understanding about what children can do at each stage of their development and so I had unrealistic expectations about their behaviors and their ability to understand what I wanted from them. They didn’t understand my rules, and I held them to expectations that were beyond their age levels.

I used to get angry when I told my 3-year-old to clean up his room and he didn’t finish the job. I didn’t realize that I needed to stay in the room with him to help guide him through the task and give him verbal support until he finished.

3. Children misbehave when they are afraid.

I used to hit and threaten my kids. I thought this was the best way to keep an upper hand and control as the parent. But I didn’t realize that when my kids felt threatened or afraid, they’d act out as a way of protecting themselves. Looking back, I should have asked them about their feelings and found ways to make them feel safe and heard instead of minimizing their feelings or telling them that they needed to get some thicker skin when they were bullied by other kids.

4. Children misbehave when they feel bad about themselves.

I grew up in a house where my brothers and I didn’t get a lot of praise and affection from our parents. Our parents loved us, but they didn’t believe in “babying” us. They said they wanted to raise us to be tough kids who would be strong enough to stand on our own feet in a cruel world. I raised my kids the same way but have come to realize that children act out sometimes because they feel bad about themselves. If kids feel bad, then they act badly. Adults have to do as much as they can to encourage children and to boost their self-esteem. Children need praise and encouragement. And you need to give them compliments for their achievements and positive behaviors instead of just harping on their misbehaviors.

5. Children learn bad behaviors by copying you.

Your children learn by watching YOU. So don’t be surprised if some of the negative behaviors you model for them show up in their behaviors. So if you curse, then it is unreasonable for you to get upset when your child uses bad language. If you yell, they will copy you. And if you hit them, then they will think it is appropriate to hit others. You have to change your behaviors and be consistent in what you teach and what you say.

Stay tuned for Mother Wit’s next blog post: 5 Reasons Why Children Don’t Misbehave.

Recent Comments