“These kids today lack discipline and they’re killing the parents!”

This is one of the popular myths I hear all the time from Black folks on social media when discussions about physical punishment come up. Far too many of us have been raised to believe anything that supports beating Black children no matter how far-fetched and illogical it is. When I hear this argument that if you don’t beat your kids they will kill you, I always scream, “SHOW ME THE DATA!”

We live in a racist country that pathologizes every aspect of Black life, and that racism is smog that we breathe in constantly. In our conversations, Black folks apply some of those same pathologies to our children. Arguments in favor of physical punishment are generally rooted not only in the fundamental belief that whuppings will serve as a protective measure from white racism, but also that our children are inherently deviant and potentially criminal. And so Black children must be contained or controlled or civilized through violence.

Because I’m sick of this kids-killing-parents argument, I decided to do a little research. Here are the facts.

There is no surge of “these kids today” killing their parents. According to data from the FBI’s National Incident-Based Reporting System, and every study that has ever been done on parricide, the killing of parents and stepparents by children is a very rare occurrence. Killings of parents constitute about 1 percent of all homicides in the United States in which the victim-offender relationship is known.

The latest study I found on “parricide” reveals that between 1976 and 2007, there were an estimated 133 offenders arrested per year for killing their fathers, an estimated 113 offenders were arrested per year for killing their mothers, an estimated 50 offenders were arrested per year for killing their stepfathers, and an estimated seven offenders were arrested per year for killing their stepmothers. Contrary to popular belief, most of the offenders were not young children or teens; the average age of offenders was between 23 and 32.

Even though Black folks like to argue, “these kids today are killing their parents,” all the studies show that parricide offenders, 73% of them, are more likely to be middle to upper-class White males. So not only is parricide a rare event in the U.S. and more likely to be committed by White males, in Black communities our children are more at risk of being killed by their parents and caretakers than being harmed by their own children.

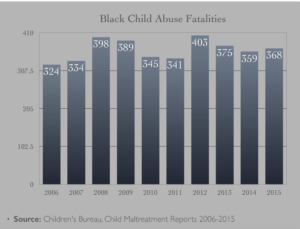

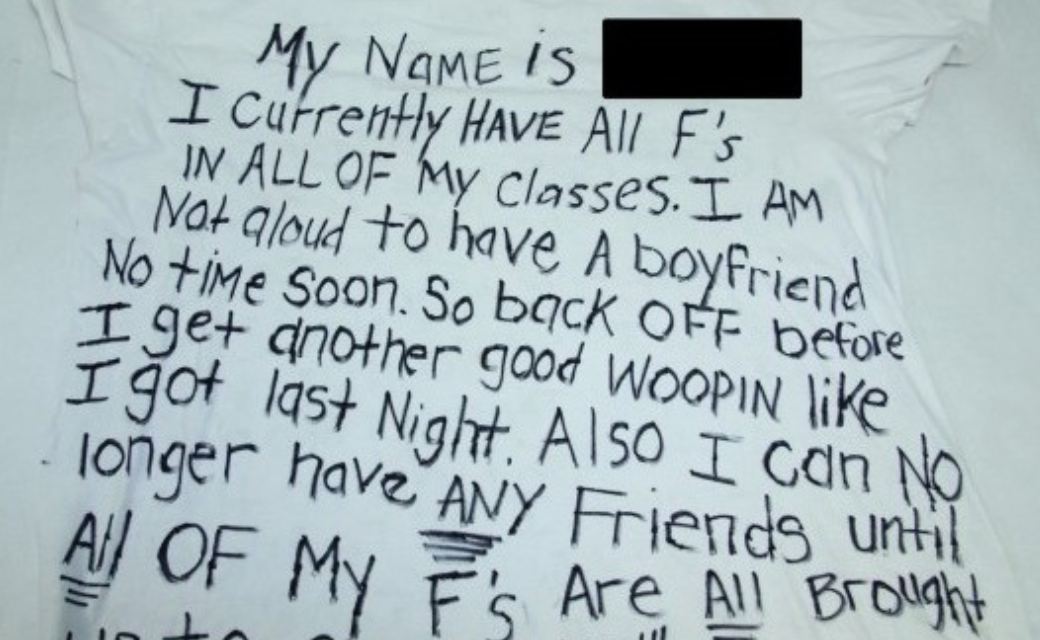

An average of 365 Black children die annually as a result of maltreatment. This is a rate that is three times higher than for all other racial groups. Most of the fatalities that occur as a result of physical punishment are not committed by sadistic parents who torture their kids. Every district attorney I have ever talked to about these fatalities has reported that the parents who kill their children did so accidently while spanking.

When there are cases of kids killing their parents, there’s usually a backstory. Here is a list of factors I’m citing from studies on parricide.

- Family isolated either by geography or behavior and life style from surrounding community.

- One or both parents substance abusers, particularly alcohol.

- Child has not been in trouble with authorities.

- Guns are the most common form of weapon. Most commonly found in the home.

- Child has told teachers, friends or someone about abuse.

- Warnings have been ignored, or law enforcement, social services and other agencies repeatedly return child to abusers. •Precipitating “triggering” event, such as sibling leaving, divorce, loss of job, change in surroundings, leads to killings.

- Crimes are ALWAYS premeditated, in the sense that abused children have thought about killing the abuser (or committing suicide) for many years.

- Crimes are always unusually violent. “Overkill” is a hallmark of parricide.

- Parent is often sleeping or in a defenseless position when crime occurs, which doesn’t fit legal definition of “self-defense.”

- Kids historically get tougher sentences for killing a parent than a parent gets for killing a child – though most do NOT receive life without parole.

I started plotting to kill my adoptive mother during my pre-teens. I did so because I wanted her to stop whupping me. I was tired of being afraid. I felt voiceless, powerless, and that I had no one to turn to for protection. With each hit I grew more angry and resentful. I always promised, “The next time she hits me I’m going to wait until she goes to sleep and I’m going to stab her.” I even fantasized about tying her up and whupping her with all the objects she every used on me: belts, switches, extension cords, a broom, hot comb, and whatever else I could pick up. I share this because I believe that assaulting a child is more likely to put a child at risk of hitting or killing a parent than refraining from spanking them because 50 years worth of studies have shown that spanking can lead to aggressive behaviors and violence.

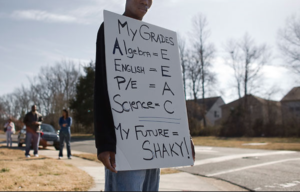

Black folks, we should be dealing with the FACTS – the horrific number of children in our communities dying each day and being facilitated through the foster care system. We should be having serious discussions about healthier non-violent alternatives to physical punishment instead of deflecting and shutting down conversations by trafficking in racist mythologies about our children.

Recent Comments