“Dear Mother Wit:

I’m having some general difficulty with my 12-year-old daughter (6th grade) and her school work. It’s 3rd quarter and I feel like I’ve been pretty patient with her in expressing the importance of getting her stuff turned in. I’m at the point where I would spank her, I am losing patience and very frustrated. I feel like I’m taking it personally and it’s making me angry that she won’t listen. Do you have any suggestions for how I may be able to relate to her in a way she will hear me?”

Dear Mom of Tween:

First, thank you for checking in and not resorting to spanking. I know how hard it is to change habits, and I’m proud of you for coming this far. One thing to remember about your daughter is that at 12 years old, she’s probably in puberty—a rush of hormones taking over her body, her mind, her emotions—all designed to drive you crazy. This isn’t an easy stage for you or for her. You nailed it when you said you feel like you’re taking her behavior personally—you’re only human! But you’re smart enough to know that it’s not personal.

Is she great in her classes, but slacking on homework?

Is she giving you a hard time about all of her homework, or just certain subjects? It could be that she needs some extra help in some subjects—maybe a tutor or scheduled time with the teacher.

Is she confident in her ability to complete her homework?

Did she used to be a good student, and now her grades are dropping?

Does she have adequate, comfortable space to do her homework that meets her studying style? Some students need quiet and solitude; others thrive being around noise and activity when they do their homework.

What about snacks or meals around homework time? Some students do better if they’ve eaten something after a long day before they start their homework.

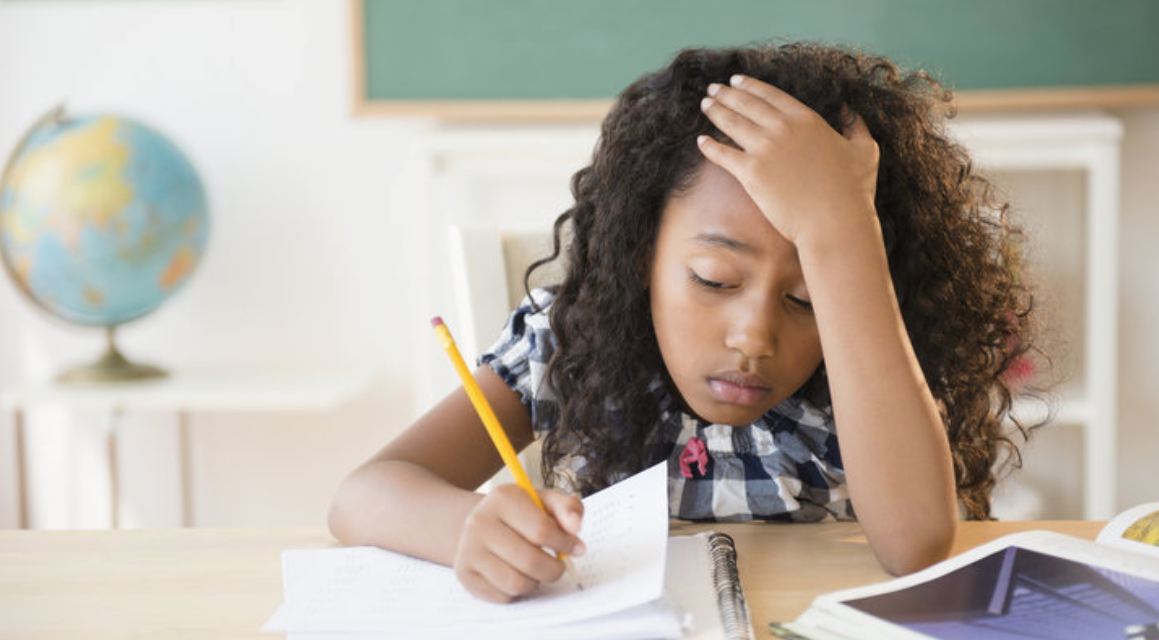

Might she have some undiagnosed learning challenges that need to be addressed, or for which she could use special help?

Here are some things that you can do to help change the dynamic that you’re caught in now:

Stop making her homework your job. If she thinks that homework is more important to you than it is to her, she won’t take responsibility.

Talk with her teacher(s) to learn where she is overall as a student. Ask the teacher if your daughter’s homework is a problem. If so, ask what the teacher intends to do about it. Have your daughter talk with the teacher about the issue or set up a conference or call with all three of you.

Let your daughter experience the consequences of her choices without getting in the way. Without nagging her or warning her—she’s already heard everything that you have to say on the topic. Let her learn “the hard way” what happens when she doesn’t do her homework.

Maybe she just needs extra motivation. You could try offering her treats for doing all of her homework throughout the week—making it fun, like a game, and not so serious all the time.

Help her learn to plan, scheduled her time and problem solve. Make it light-hearted and fun and consider rewards for when she does what she’s supposed to.

Finally, STOP reminding her to do homework. Stop asking her about homework. Stop talking about it at all. Let the teacher(s) know that you’re doing this so that your daughter can experience the natural consequences of her choices.

Plan the consequences if she doesn’t do all of her homework each week. Set up a notification system with the teacher (email is great for this) so you’re able to keep track. Be calm and consistent in applying those consequences—like taking away privileges or things that she enjoys.

You can also try positive, pleasant motivation: special treats or outings when she DOES complete her homework. Some people are motivated by prizes!

I hope you can try these different things and wish you the best of luck in getting your daughter to do her homework. She’s at an age where it’s natural and healthy for her to rebel against you and your rules in at least one area of life. The key for you is to stay as calm as possible (and put some stress relief and management in place for yourself), and to be consistent in what you are asking her to do.

Please check back in and let me know how it’s going! I’ve got faith in you and your daughter.

Hugs,

Mother Wit

Don’t hit the kids, hit the keyboard. For more parenting tips, or to get parenting advice please visit www.sparethekids.com.

Recent Comments