I’m sharing this piece that I wrote for www.forharriet.com earlier this week. While the aim of this piece is to demonstrate how the fixation on white babies and a white future through controlling white women’s reproductive activities is connected to discrimination and amped up violence against people of color, I felt it was important to share with STK’s audience. Parents, black or white, who are raising children of color need to understand the context under which they are raising their sons and daughters…..

By Stacey Patton

The GOP’s war on the most intimate aspects of women’s lives is undoubtedly real, but it is not being applied without discrimination.

Let’s be clear—the primary targets of the right wing’s rhetorical and legislative attacks are, and have always been, white women. The war on white women is really a push for more white babies. And, that push goes hand in hand with amped-up racial profiling, vigilante policing, mass incarceration, school closures, hoarding of resources from communities of color, and blatant disregard for violence directed at African Americans and their children, including the unborn.

More white people are dying than are being born, a trend that is projected to continue. Meanwhile, the birth rates for people of color remain stable or high, primarily for Latinos. The trick for the modern American situation is to prevent people from seeing that the war for more white babies and the war against people of color are related. But the two phenomena are inseparable.

What we are witnessing is not new, but rather a familiar pattern of desperate efforts to preserve white domination through strength in numbers. It is an historic fact that when radical demographic shifts take place in the United States they are accompanied by white supremacist fears of being outbred and crowded out by immigrants and people of color, and losing majority rule.

And so here we are again. America is undergoing yet another periodic age of white fear and cradle competition. As the white population marches toward a less than majority status, the constant fear of biological extinction has infected our political discourse, policy decisions, and everyday racial interactions, whether in the comments sections of news sites or in the streets.

For those who remain skeptical about the association between fears of white race suicide and emphasis upon women’s reproductive roles, consider the words of famous and respected persons such as Teddy Roosevelt, a champion of race purity who with little embarrassment called black Americans “a perfectly stupid race that can never rise.”

Responding to the falling white birth rate, in his 1906 state of the union address Roosevelt blasted elite native-born white women for shirking their national civic duty to be mothers of the nation by engaging in “willful sterility—the one sin for which the penalty is national death, race suicide.” In his eyes, a white woman who avoided having babies was a “criminal against the race” and “the object of contemptuous abhorrence by healthy people.”

Later, in a 1913 letter to the prominent eugenicist Charles B. Davenport he wrote: “Society has no business to permit degenerates to reproduce their kind…. Some day we will realize that the prime duty, the inescapable duty of the good citizens of the right type is to leave his or her blood behind him in the world; and that we have no business to permit the perpetuation of citizens of the wrong type.”

Roosevelt’s declarations came at a time when more women were pursuing education, seeking careers, voting rights, greater voice in public life, and control over their own fertility. All of these factors supposedly made women physically unfit to be good wives and mothers. Doctors of the era argued that the pursuit of higher education, participation in sports and professional life diverted too much blood to women’s brains from their reproductive organs.

Meanwhile, all this discourse was attendant by race riots, lynchings, unpunished rapes of black girls and women by white men, and other forms of genocidal violence. In 1918, in Valdosta, Georgia, an angry white mob hung an 8-months pregnant Mary Turner upside down by her ankles, doused her with gasoline and set her on fire. While still alive, a man in the mob split her swollen abdomen with a hog knife, and stomped the fetus to death before the rest of the mob riddled Turner’s body with bullets. That same year a mob of whites hung Maggie and Alma Howze from a bridge near Shutaba, Mississippi. Both had been raped by the same white man and were pregnant with his children at the time of their lynching.

Consider also Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood who believed that eugenics and birth control could prevent “biological and racial mistakes.” This contradictory historical figure saw no problem with seeking funding and support from the Ku Klux Klan. The eugenics movement was about encouraging the “fittest” to reproduce and directed toward eliminating undesirables. While thousands of black females, white “degenerates” and “ morons” were legally sterilized in the early 20th century, smut suppressors like Anthony Comstock led successful campaigns to make it illegal to send birth control literature through the mail.

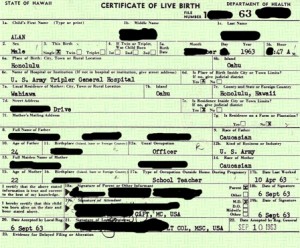

Flash forward to the Obama era.

Since 2011, state legislatures across the country have introduced hundreds of provisions from “heartbeat bills” and fetal pain laws, to encouraging violence against abortion doctors and reducing women’s access to birth control and abortion services. Some right-wing politicians have even sought to redefine rape in a way that would force female victims to carry the fetus to term. Their twisted rationale is that an unborn child should not have to die because of a rapists’ crime.

Last April, Kansas Republican Gov. Sam Brownback signed a bill that bans sex-selection abortions, blocks federal tax breaks for abortion providers, forbids them from giving educational talks to students, and declares that life begins “at fertilization.”

What will we witness next—a new bill introduced, in a majority-white state of course, declaring that life begins when a man gets an erection? Will Republicans start citing Genesis 38:9 to criminalize men for masturbating and “spilling their seeds” to prevent conception? Okay, I’m being facetious here. But in fact, almost nothing is directed against controlling the sexual behaviors of men, including rapists, unless of course you are a black man accused of some sexual indiscretion with a white woman. But generally, the burden of sexual morality is placed on women.

Perhaps the worse political gaffe came from Indiana Republican Richard Mourdock, who said he opposed aborting pregnancies conceived in rape because “it is something that God intended to happen.” Are these politicians and their supporters so desperate to boost the population of white babies that they’ll even take those conceived through rape?

While Republicans and Democrats debate the war on women, they have remained conspicuously silent about the intensifying war on black adults and children. If you want a demonstration of the devaluing of black children even as white women of our time are forcibly pushed towards procreation, just do a quick Google search of police assaults against pregnant black women and you’ll see what I mean. There are news stories and graphic videos of visibly pregnant women being cursed at, punched, tasered, kicked, and body slammed to the ground by white police officers.

Though most of the babies were born uninjured, 17-year-old Kwamesha Sharp wasn’t so lucky. In June 2012, Sharp lost her unborn child when a Harvey, Illinois police officer slammed her to the ground and kept his knee pressed down on her abdomen for an extended period of time. According to court documents the arresting officer, Richard M. Jones, said he didn’t care that Sharp was pregnant. In a few of the other cases, the women were arrested and charged, and the officers’ superiors backed their actions.

A new video recently surfaced on social media showing a young black mom, who may have been drugged and raped, being strapped down to a chair inside a Warren, Michigan police station, where one officer kicked her and another chopped her hair off with a pair of scissors.

In addition to physical attacks, black mothers have been fined and jailed for “stealing” education for their children by enrolling them in safer suburban schools. Black parents have had to bury their children. Their names have made headlines: Oscar Grant, Trayvon Martin, Kimani Gray, Darius Simmons, Jordan Davis, Renisha

McBride. Meanwhile, mass school closures in Chicago, Philadelphia and other urban districts across the country have disproportionately targeted and destabilized children in poor black and Latino communities.

The war on black children and teens is especially mean-spirited. A litany of examples makes me think of what civil rights doyen W.E.B. DuBois wrote in 1920: “there is no place for black children in this world.”

Former Idaho executive Joe Rickey Hundley made headlines last February when he slapped a crying toddler on a Delta flight headed from Minneapolis to Atlanta. Hundley told the adopted child’s white mother to “shut that nigger baby up.”

Last September, a white Texas man shot 8-year-old Donald Maiden Jr. in the face while he played tag with other children. In November, New Mexico police officers smashed out the windows and recklessly fired shots into the fleeing minivan containing Oriana Ferrell and her five children who range from age 6 to 18. The mother said she fled the scene during the wild traffic stop because she feared for her children’s safety.

Just last month, 16-year-old straight-A high-school student Darrin Manning was on his way to play a basketball game when he was stopped and frisked by a Philadelphia cop. During the search, a female officer squeezed his genitals so hard that she ruptured his testicles, rendering him sterile.

Today’s white supremacists aren’t necessarily as inflammatory in their language about race and sex. But a century ago, as now, they have never spoke about increasing the births of nonwhites, protecting the black unborn, or setting progressive economic and social policies to make the world a safe place for them to thrive once they are born. Remember when former education secretary Bill Bennett said that aborting every black infant in America would lower crime rates?

So here we are in 2014. The United States has already reached a tipping point in its ethnic and racial diversity. More than half of all babies born in this country are children of color. By 2018, the majority of all children nationwide are projected to belong to nonwhite groups.

These numbers, along with enduring white supremacist fears of dying out culturally and biologically, are the real reasons behind the GOP’s so-called “war on women,” and the continuing attacks on black adults and children. When we take a step back and widen the lens we are able to see how injustice, whether it is based on gender or race, grows from the same insidious root cause.

Dear Bullied’s Mom,

Dear Bullied’s Mom,

Recent Comments