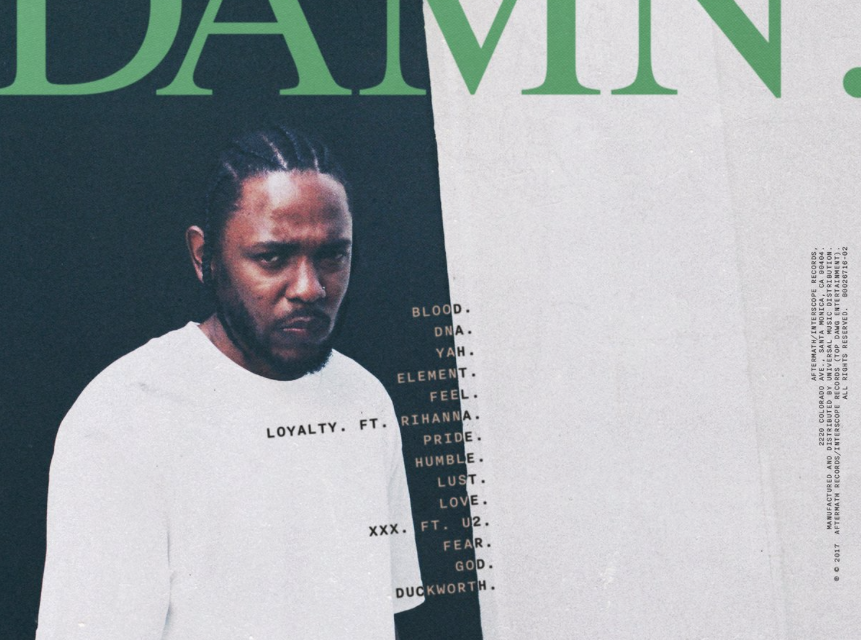

I finally got a chance to listen to Kendrick Lamar’s “Fear,” a feature song from his new album ‘Damn.’

The song takes us on a journey through his developmental stages of fear, beginning with his childhood at age 7, then 17, and 27. Each stage represents a window into Lamar’s awareness of how the toxic smog of white supremacy poisons Black life at every turn, especially our intimate and social relationships with each other.

Lamar’s lyrical analysis of his own life cycle reveals that Black folks never age out of fear because at each developmental milestone we are met with new amped up forms of devaluation by the state, other Black folks who are walking around as victims of unrecognized traumas, and from the people who are supposed to love us and provide a refuge from hate and violence.

In a recent Facebook post, I griped about how I hear so many Black parents sowing the seeds of fear in their children early on. I wrote:

It really unnerves me when I hear black people say, “I want my child to fear me.”

Why?

There’s already so much racist ugly in the world for them to fear. There’s already so many mean-spirited people in the world who hate and want to destroy us. Why, as their giver and nurturer of life, would you want to put yourself within that spectrum of angst and devaluation?

And from a scientific perspective, fear is a form of chronic stress that activates biochemical responses in your child’s body which moves them into maximum alert in times of threat, and they don’t always immediately return to normal levels.

Fear causes inflammation throughout the body and prompts biological changes that can affect the immune, vascular, metabolic and endocrine systems, and can prompt their cells to age more quickly. This cumulative wear and tear – known as an “allostatic load” – can negatively impact your son or daughter beyond childhood, and even the future health of their children because stress also causes genetic changes.

Fear is killing black people. And I’m not being hyperbolic. Just take a look at any report on health disparities. The foundation is often laid with the accumulation of toxic stress that begins in childhood.

The fear, the pain and damage of unresolved childhood traumas is the bitter root of most of what ails our communities: child abuse, domestic violence, sexual exploitation, misogyny, misandry, phobias, substance abuse, and dare I say so much of our political fecklessness. So many of us are walking around saying, “I turned out fine.” But really, so many of us are victims of unrecognized trauma.

If we prime our children to fear the people who love them most and teach them that obedience is survival and their greatest virtue, then how can we expect to raise future generations of young people to engage in effective resistance against our enemies?

Fear does not equal respect.

A few days later, a number of folks sent me messages on Facebook: “Did you hear Kendrick Lamar’s new song? He talks about beatings.” So I begrudgingly decided to check it out, thinking that it was going to be yet another one of those rap songs by a Black male artist thanking and celebrating his mama for hurting his body to prepare him for a cruel racist world.

Here’s that verse folks were telling me about:

“I beat yo’ ass, keep talkin’ back

I beat yo’ ass, who bought you that?

You stole it, I beat yo’ ass if you say that game is broken

I beat yo’ ass if you jump on my couch

I beat yo’ ass if you walk in this house with tears in your eyes

Runnin’ from poopoo and ‘prentice

Go back outside, I beat yo’ ass lil nigga

That homework better be finished, I beat yo’ ass

Yo’ teachers better not be bitchin’ ’bout you in class

That pizza better not be wasted, you eat it all

That TV better not be loud if you got it on

Them Jordans better not get dirty when I just bought ’em

Better not hear ’bout you humpin’ on Kiesha’s daughter

Better not hear you got caught up, I beat yo’ ass

You better not run to your father, I beat yo’ ass

You know my patience runnin’ thin

I got buku payments to make

County building’s on my ass

Tryna take my food stamps away

I beat yo’ ass if you tell them social workers he live here

I beat yo’ ass if I beat yo’ ass twice and you still here

Seven years old, think you run this house by yourself?

Nigga, you gon’ fear me if you don’t fear no one else”

I won’t dissect the entire song, but I’ll focus on that first verse because it is yet another testimony of a Black male rapper reflecting back on his mother’s cruelty and how that pain has continued to reside within his body and spirit as a grown man. What it reveals is how a Black boy had to grow up under constant attack, on guard, and unconsciously reacting to his own repressed past.

Sadly, like many young Black males, Lamar’s first experiences with cruelty and humiliation came at the hands of his mother. But unlike other artists before him, Lamar does not celebrate his mother’s cruelty by calling her a “queen,” thanking her for the beatings, and crediting mother-perpetrated violence for his success.

Lamar is different from the Black boys and men that have for generations accepted the internalized “lie” that slavery, Jim Crow, and racist policing practices requires cruelty to protect Black children, especially males, from their own impulses. While his mother tried to conceal her cruelty to justify the beatings, a more honest truth emerges from Lamar’s lyrics: he never associated the beatings and the fear with safety and comfort and love.

I’m going to go out on a limb and say that Black mothers who whup their sons and terrorize them in early child do not truly realize the damage they are doing. And yet, the racist notions of Black boys as deviant and violent are ultimately reinforced by parents who are doing their best to minimize the stressful realities of poverty, racism, sexism, and inequality.

Like many folks in the Black community, his mother may have rationalized her violence against her son by calling the harsh discipline an expression of love that ultimately kept him safe and led to his success. But this kind of denial and justification, and even much of the joking about being whupped, feeds the cycle of abuse in Black communities and drives the truth about our traumas underground.

Think about Ghostface Killah’s song “Whip You with a Strap,” from his 2006 album Fishscale. He recalls his mother’s response to his temper tantrums:

“Take me across her lap, she used to whip me with a strap

When I was bad

Bad

Take me across her lap, she used to whip me with a strap When I was bad Bad

Picture me snotty nose sittin on my aunt’s lap

The kid like 5 or 6 shit I will curse back

I got it from the older folks sittin in the living room

Everybody had cups stylistic song boom

But then came Darryl Mack lightin’ all the reefer up

Baby caught a contact I’m trying to tie my sneaker up

I’m missing all the loops strings going in the wrong holes

It feels like I’m wobbling, look at all these afros

Soon as I thought I was good the joke’s on me

I heard a voice “get in the room, I get angry”

Sting my feet catch a tantrum

Spit, scream, fuck that

Momma shake me real hard, then get the big gat

That’s called the belt help me as I yelled

I’m in the room like (panting)”huh, huh, huh” with mad welps

Ragged out, bad belt yes her presence was felt

Then get my black ass in the bed it’s time crash out (crash out)

Take me across her lap, she used to whip me with a strap

When I was bad

Bad

Despite the alcohol, I had a great old Mama

She famous for her slaps and to this day she’s honored

But when I was a lil dude her son was a lil rude

I picked the peas off my plate and pour juice in her nigga food

Get beat, then I’d run and tell grandman “mama hit me for no reason”

She whipped me hard when I finished eatin

And felt that belt stingin after I wet that bed

Hid my drawers and start cryin, when she felt that bed

Caught another when I told her those the fake pro-keds

In the corner weavin and screamin trying to block my head (ahHH!)

Nowadays kids don’t get beat, they get big treats

Fresh pair of sneaks, punishments like have a ceas

Back then when friends and neighbors would bust that ass

And bring you back to your momma she got the switch in the stash

That’s back to back beatings

Only went outside for free lunch with welts on my legs still leakin yo

Take me across her lap, she used to whip me with a strap

When I was bad

Bad”

While the cruel Black Mama is often placed on a pedestal, innocent black women ultimately become the targets of this repressed rage accumulated since boyhood. As Howard University Law School professor Reginald Robinson has noted, “that cruelty gets repressed, surfacing again as nearly autobiographical lyrics because these artists uncon-sciously need to reveal the truth of their cruel sufferings to others, and they need others like enlightened witnesses to validate their lyric-based personal histories, without at the same time directly confronting their cruel mothers.”

He further explains that these artists, who may not have been touched lovingly as children, become hyper-masculine as a defense mechanism as they relive their painful childhood experiences through their music. They’d never admit to it, but these men really want to assault the mothers who were the first to hurt and emasculate them.

It’s important to emphasize that black men are not born hating black women. It is the trauma they suffer that teaches them the need for self-preservation. But there are very few spaces for black men to talk about their trauma and pain other than through comedy, rap music, or nostalgic anecdotes about being whupped and turning out fine. Even speaking about their abusive experiences at the hands of Black women is often considered misogynistic.

I hope that folks will really listen to each verse of “Fear” and understand how the insanity of white supremacy requires the destruction of Black children physically, emotionally, psychologically and spiritually. And the greatest trick of all is to invite their loved ones to participate in the process.

If we are ever going to become more politically effective warriors in the fight for racial justice, producing children who live with toxic fear in their body is the very last thing that Black America needs.

I just had this conversation last night. So many women fail to realize that just because an artist is praising his mother for beating him doesn’t mean that it was the right thing to do. It just means that he doesn’t understand what it has done to him and he doesn’t have any positive experiences to compare it to. The deflecting and willful refusal to take responsibility for this type of behavior is a huge part of the problem in the black community. Black women only want to hear that they are God and Queens. Any CONSTRUCTIVE CRITICISM is seen as you “hating black women” which is absurd. No one is above being critiqued and correction. To see it as anything other than what it is speaks to the delusional state of mind so many black women walk around in.

And so the stereotype of a man does not understand his own frelings and life experiences continues to go on here. All of this information is okay yet it is done from a third person perspective. Why not actually talk to men and mothers and get their take on it. Saying I want my child to fear me not automatically terrorizing. It could they gonna you can’t play around and that I’m. I bet you, you interview those women and fear will not stand up to the use it is stated here. Of course we know what fear does to the body yet that is general fear, not parenting fear different things.

You are truly a force to be reckoned with Ms. Patton! Keep fighting the good fight❤️

Black fathers are noticeably absent in this article, and perhaps, in the lives of children who are victims of this type of abuse. The presence of TWO fully supportive, committed parents can mitigate the stress (and it’s negative effects) that come with raising children in a racist world. The abuse, neglect, or absence of either parent impact black women and black men alike.

I am an african american male and I am currently researching and anaylzing this phenomena .

I difinitely had a mother who beat me regularly.

Another part we need to look at is not just the role black women play in the way they raise thier childern, but also the role white people play in enforcing this pathology